Sex in the City

& Memoirs of a Geisha:

The Way of Tea(se)

From KJ 64, Gender in Asia

BY LAUREN W. DEUTSCH

BY LAUREN W. DEUTSCH

Here’s a refreshing thought: ImagineMemoirs of a Geisha, the Hollywood blockbuster film version of Arthur Golden’s novel, made by the folks who created the American sitcom Sex in the City.

Here’s a refreshing thought: ImagineMemoirs of a Geisha, the Hollywood blockbuster film version of Arthur Golden’s novel, made by the folks who created the American sitcom Sex in the City.

For those not familiar with SitC, hajimemashite…

Carrie, Miranda, Samantha and Charlotte are four self-determined, attractive, fashionably attired 30+-something upscale female Manhattanites. Successful in their careers, they are financially able to enjoy many of the material benefits that the city has to offer – including high-fashion clothing, nice apartments, cab rides, cover charges and good tables at the hippest eateries, performing arts events and, in one case, even being a single mom. Unlike Woody Allen’s classic characters, they are not apologists or angst-ridden. Nor are they desperate housewives. What’s even more interesting is that they are quite capable of leading reasonably well-balanced lives even when not in relationships – sexual or otherwise – with men. But finding the ‘right’ man is the binding theme. These women regularly check in with each other – usually over a meal or cocktails – exchanging news of their careers and their latest exploits in and out of romance. They offer each other compassionate commiseration and practical support, sometimes even disagreeing and being judgmental, but in a constructive manner. Unlike stereotypical “chick flicks,” to the writers’ credits, their conversations are not dumbed-down gossip. Rather, they reflect consciously upon social ethics and mores of the lives of the people around them and their own.

Most importantly, the quartet presented have succeeded in breaking through the “gender-role ideologies about romantic heterosexual love, which depict friendships between women as very much second best.” In short, they are true ‘girlfriends,’ there for each other, 24/7. Each has a sense of her uniqueness, power and vulnerability in a complex world that isn’t strictly male-defined (anymore). They are as interested in their interests in men as they are in the men they are interested in.

Just as geisha inhabit Kyoto’s labyrinthine Gion district, these women are classic cosmopolitan New Yorkers who know their way around the ‘hood. The show could just as easily have been called “The City and Sex”

in its attention to detail of New York’s upscale ambience – its tony avenues and social ‘scenes.’ While there’s nothing so gauche as yesterday’s high fashion, I predict that the show will prove to be a classic, just like the little black dress.

The program is honestly, not stupidly or violently, about sex. When it premiered on HBO Cable it was weekly; not too much focus on sex for four vital women. Watching it seven days a week marathon one doesn’t OD on either ‘sex’ or ‘city.’ This goes to show how the topic can be interesting and diverse, especially when placed in the context of interesting lives. Their collective concerns are easily recognizable to most women: to marry or not, to have a baby or not, to see an old beau again and make up, make out or just do unto-him-what-he-once-did-unto-her. Even with the network TV censors’ heavy hands busily snipping steamy scenes, the original broadcaster’s manifest destiny is easily imagined. And when the going gets tough, the tough can always go shopping.

Memoirs of a Geisha could have been presented within this paradigm: to explore in good story-telling fashion the intimacy and fullness’s of one geisha’s life from the inside out. But no! The filmmakers fashioned yet another Orientalist representation of traditional Asian femininity crafted in the frozen imagination of a Western man. If the filmmakers thought they could hide behind a papered shoji, they were sorely mistaken. What a waste of an opportunity, not to mention millions of dollars.

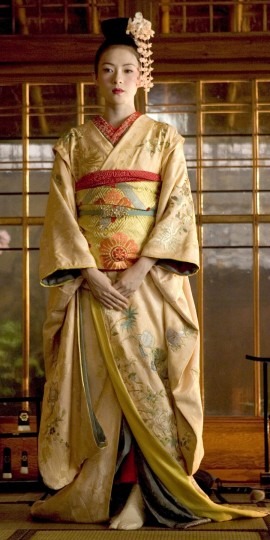

That said,Memoirs of a Geisha is not much more than another Asian martial arts film with great costumes and sets. MoG boasts that a real geisha can stop an unsuspecting man dead in his tracks with a single potent glance. The weapon of choice is the ‘tease,’ rather than a sword or bow or even a craftily-wielded chashaku (tea scoop). Sounds ninja or samurai-ish to me.

The Way of the Tease, like geishahood itself, is a complex life lived according to a strict aesthetic code. It’s practice honed through a lifetime of gaman (endurance), and perfected through endless training and practice, like any other -do (aikido, shodo…). And it demands nothing less than total commitment to teacher, patron, ‘school’ and creed.

MoG suffers a spiritual void by losing touch with the inner power of the geisha. As real-life geisha Mayumi reflects in Jodi Cobb’s exceptional book, Geisha: The Life. The Voices. The Art, “A geisha contains her art within herself, and because her body has this art, her life is saved. That is the power of art – the salvation of one’s soul.”

The film MoG had no soul.

It would have enriched the story if we were reminded that this profession is a living art, an expression of the refined qualities of Japanese culture. There’s no reason to suffer so much to learn to play the shamisen. I understand the ultimate point of the argument that geisha are not prostitutes or courtesans, but I concur with the wise person who observed, “If they say it’s not about sex, it’s always about sex.”

Taking more than five years to make, the exhaustively-hyped premiere blushed in time for the 2006 Academy Award season. The result is as flat as an ukiyo-e woodblock print in the style of a souvenir postcard from a frazzled rather than floating world.

In both the film and book, young Chiyo is sold by her poor father to a peddler in virgins, and, is in turn, indentured to a renowned geisha house. The film places it in “Hanamichi,” a mythical Gionesque neighborhood of an equally mythic Kyoto-ish place called “Miyako.” This Meiji Cinderella story has the requisite stepmother, older ‘evil’ stepsisters and even a Pumpkin, the name of Chiyo’s sempai.

With almost “Whistle While You Work” resignation, Chiyo endures her servitude and even seemingly takes a liking to her performing art lessons. One enchanted day, she meets up with the dashing Prince Charming of her future who ignites her little girl heart (and cools her exhaustion) with a gift of bean-flavored shaved ice. Looking into her beautiful, dark eyes, he tickles her imagination by telling her that she could grow up to be a geisha one day, like the two lovelies (They giggle.) accompanying him. (They giggle again. Yes, with fingertips together screening the lips.)

Almost bewitched, Chiyo vows to seize her fate by its horns and to charge him with the responsibility to liberate her from indebtedness to her mistress through his intervention alone. In pure Hollywood style the film processes quickly through geisha turf wars, rape, extreme poverty, the Pacific War and the culturally inept American Occupation forces. Eventually Sayuri lives happily ever (and not a moment before). In the words of “Eliza Doolittle” the waif-turned proper socialite in the Broadway musical My Fair Lady, “A-o, u-dden eetu bi roberu-ri.”

The producers made a point of insisting, “It’s not a documentary … not a documentary … not a …”. No one thought it was going to be. The geisha whose life the original book was supposed to trace disowned even the well-crafted novel. But at least the book offered details of the angst and sadness that mirrored the early years of so many geishas’ lives.

If Steven Spielberg had directed, which was the initial plan, the audience might have been pressed to cry real tears as the young Chiyo climbed up to the okiya roof in a valiant attempt to escape back to her parents. There, true to form, he might have had Chiyo meet a friendly tanuki-san who looks not surprisingly like ET.

The press kit further boasted that the filmmakers were under some kind of ‘spell.’ According to director Rob Marshall, “I knew that the drama of these characters, combined with the allure and exoticism of their world, would veer from tradition when it was necessary to serve my vision of the story. I needed to thoroughly understand the reality first.”

The production team visited a geisha teahouse, sumo match and kabuki performance and soaked up the quaint vibe of the jewel that is Kyoto. There’s mention of the filmmakers consulting with gaijin geisha anthro-apologist Liza Dalby. Perhaps she was only consulted on the clothing, walking, and other production elements. All we see is see is stereotypical tourist trade.

There’s no mention either that they sought to understand the fundamental agony of young girls in the sex slave trade, a world that exists today in so much of Asia and other Third World cultures. How about selling one of their pre-teen children to one of Japan’s performing arts academies, such as those that run something like a reform school for and by the Takarazuka Review. (See my review in the print edition of this issue.) We’re not talking about after-school tap dancing or acting lessons encouraged by stage moms.

Going back to the Sex in the City model, the filmmakers could have given the story a new turn, to allow the geisha to speak openly. A good source of information would have been Jodi Cobb’s aforementioned, splendid non-fiction book. In it, Yuriko, a geisha house okamisan, tells of her miserable life, just like that of Chiyo. At the age of 19, Yuriko had mizu-age, the apprentice geisha’s first sexual experience; hers with a client who was 72 years old. “It now seems like sexual harassment,” Yuriko recounts. (Not a documentary … Not a documentary … )

A film doesn’t have to be a documentary to show how impossible it is for fragile paper, wood and tile architecture to shelter raging egos and hormones and secure the deepest secrets. Even with all that potential energy, the scenes had no ‘heat.’ In one instance, the reigning drama queen of the okiya stable, Hatsumomo, consumed in jealous rage that her former junior, now the fully initiated “Sayuri,” is poised to eclipse the senior’s chances to inherit the business. At once, Hatsumomo heaves a lighted lantern against the tatami, starting a fire. Anyone who has visited Japan knows that such a blaze would wait for no cue, much less “CUT!”, even from a famous Hollywood film director. It would take the neighborhood down with it. Maybe fantasy burns much slower.

Director Marshall reserved the most furious moment for Sayuri’s debut at the annual geisha coming-out dance performance. Her solo was a mad wild mustang rant with hoof-like zoris pounding on stage like a dance version of Equus. The scene was more fashion show runway than a Pontocho-esque theater. We are informed that from this point on that Sayuri became the toast of the town. Was the choreography supposed to be her release of years of pent up anger? I venture to project that would have scared your basic Meiji baron to death. What man would have the courage to even get near her?

On the melancholy side, the film was drowning in references to water; it always seemed to be raining. But rather than artfully capturing a few raindrops on old tile roofs, the filmmakers drenched hope and that made for soggy subtlety.

For all the ingenious lighting tricks and artfully fabricated sets establishing a faux teahouse neighborhood in the mountains north of Los Angeles, the crafting of new lamps from old fragments, it was all Hollywood artifice. The great shadow master, author Tanizaki Jun’ichiro, saw it coming, “Westerners attempt to expose every speck of grime and eradicate it, while we Orientals carefully preserve and even idealize it.”

Clearly attracted to the external beauty of the Japanese aesthetic and Oriental women in general, the White male filmmakers never understood the roots or depth of its perfection, rather succumbing to the perfection of their own egos.

Truth be told, the real love of Geisha’s life is “Oscar”tm, a Hollywood samurai whose long sword and Kinkakuji patina can stop a filmmaker dead in his or her tracks with just one nomination nod. As I wrote this, the Academy Award short lists had just been announced, with MoG honored in six predictable production categories: Cinematography, Art Direction, Original Score, Makeup, Costume Design and Sound Editing.

I have some additional categories to expand the universe.

Best Lasting Impact in Fashion: “I think the low neckline in back will definitely be noted by the fashion world again soon,” said Costume Designer Colleen Atwood. How low can you go? A year later, I can report no such trend.

Best English as a Foreign Language Film: This wasn’t one of those old fashioned Occidental productions where the Ls and Rs are mixed in comic relief. It was a hybrid of sounds that the pan-Asian cast could barely muffle and native English speakers, understand. This faux pas puts it into an additional category:

Best Film to Rekindle Old Feuds: Tied with Spielberg’s Munich. The film may not be released in China because of the casting of Chinese actresses in the Japanese role.

Best Geisha Metaphor by a Film Critic: Richard Rushfield, another Los Angeles Times staff writer, penned, “The Road to the Nominations Announcement, however, starts at midnight with a minutely choreographed kabuki dance in which the academy theater opens to the production staff, the Hollywood press and to me, who comes to watch the ritual unfold.”

Best Truth-Be-Told by a Film Critic: Carina Chocano in the Los Angeles Times wrote: “By the time Sayuri asks, ‘What do we know about entertaining Americans?’ You want to say, ‘Honey, please, you’ve been doing it for two solid hours.’