by Brother Anthony of Taizé and Hong Kyeong-Hee

(2007. Univeresity of Hawai'i Press. Honolulu.)

Reviewed by Lauren W. Deutsch

KYOTO JOURNAL 71

“Too fussy,” observed a member of the audience watching the formal presentation of the “Korean Tea Ceremony” at the consulate’s culture center in Los Angeles. The demonstration by members of the local Korean tea culture group was consciously but gracefully paced and helpfully narrated by a young woman dressed in hanbok, traditional jacket and skirt. A grass mat was spread in front of a display of a “woman’s room” of a literati class family, a landscape painted screen stood to one side and gayagum music filled the air. Having studied chanoyu, Japanese tea ceremony, for 25 years, I can attest that the preparation effort seemed anything but “fussy”. In fact, it looked particularly natural in its economical movements and resulted in a few sips of yellowish liquid that tasted warm and soft on the palate. Not fussy at all.

“Too fussy,” observed a member of the audience watching the formal presentation of the “Korean Tea Ceremony” at the consulate’s culture center in Los Angeles. The demonstration by members of the local Korean tea culture group was consciously but gracefully paced and helpfully narrated by a young woman dressed in hanbok, traditional jacket and skirt. A grass mat was spread in front of a display of a “woman’s room” of a literati class family, a landscape painted screen stood to one side and gayagum music filled the air. Having studied chanoyu, Japanese tea ceremony, for 25 years, I can attest that the preparation effort seemed anything but “fussy”. In fact, it looked particularly natural in its economical movements and resulted in a few sips of yellowish liquid that tasted warm and soft on the palate. Not fussy at all. Korea has had a “Way” of tea but it hasn’t been widely seen, much less described or studied by foreigners. This new guidebook full of color illustrations, created by Brother Anthony and Hong Kyeong-Hee and published by Seoul Selection (available online), is a welcome edition to one’s tea or Korean culture library.

Korea has had a “Way” of tea but it hasn’t been widely seen, much less described or studied by foreigners. This new guidebook full of color illustrations, created by Brother Anthony and Hong Kyeong-Hee and published by Seoul Selection (available online), is a welcome edition to one’s tea or Korean culture library.

The book is a labor of love produced by two simple, cultured gentlemen whose relationship has been refreshed again and again over cups of tea. Having enjoyed tea with them in Mr. Hong’s Anguk-dong residence, I could imagine these two literati having met centuries ago, the former a renowned translator of Korean poetry and literature into English and the latter an unassuming scholar / teacher of letters.

Beautifully illustrated and filled with poetry, history, science and anecdotal material, the book itself feels like the un-fussy nature that one associates today with enjoying a cup of carefully prepared Camelia Sinensis, seated on a floor pillow or low stool in one of the many tiny, rustic tea rooms crammed one upon and next to another in Seoul’s Insadong antique district.

Beautifully illustrated and filled with poetry, history, science and anecdotal material, the book itself feels like the un-fussy nature that one associates today with enjoying a cup of carefully prepared Camelia Sinensis, seated on a floor pillow or low stool in one of the many tiny, rustic tea rooms crammed one upon and next to another in Seoul’s Insadong antique district.

The contents of the book constitute a refined and expanded text developed from the “blog” presented by Brother Anthony on his website. The site contains an index, links to his articles in the Korea Times and other tea sites.) A “congratulatory” message from tea master Chae Won-Hwa, founder and head of the Panyaro Institute for the Promotion of the Korean Way of Tea, certifies the authenticity of sentiment and literal meaning of their words.

During Korea’s 19th – 20th century Colonial Period, the Japanese were happy to lay claim to Korea’s tea resources as they did the potters who were taken back to Japan to support their burgeoning Japanese tea culture in the 16th century. While some Koreans pride their culture as lacking the “fuss” usually associated with Japanese arts, this does not mean it lacks form or focus. From the growing of tea leaves and their processing for packing, to the preparation of self and leaf into beverage, Zen Buddhist philosophy – Seon Cha – as well as the courtly arts may be infused in every leaf and gesture.

During Korea’s 19th – 20th century Colonial Period, the Japanese were happy to lay claim to Korea’s tea resources as they did the potters who were taken back to Japan to support their burgeoning Japanese tea culture in the 16th century. While some Koreans pride their culture as lacking the “fuss” usually associated with Japanese arts, this does not mean it lacks form or focus. From the growing of tea leaves and their processing for packing, to the preparation of self and leaf into beverage, Zen Buddhist philosophy – Seon Cha – as well as the courtly arts may be infused in every leaf and gesture.

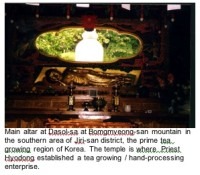

Panyaro (“’Dew of Enlightening Wisdom”) green tea is meticulously grown on and hand-processed at a plantation near Bomgmyeong-san mountain in the southern area of Jiri-san. Chae Won-Hwa has formalized a rltual for preparation also, interpreting the manner taught to by her teacher, the Venerable Hyodang, head monk of Dasol-sa temple near Jinju. This temple is still a source of fine hand-made tea, and wild tea plants may be found along the mountain slopes.

Tea, like Korean cuisine in general, was also enjoyed in a courtly manner by ladies and gentlemen who attended the royalty, so naturally, there were appropriate embellishments, such as in the utensils and manner of offering the beverage to their Esteemed Majesties. Such external “fuss” may have been implied in the Los Angeles demonstration critique but the preparatory manner was clearly well-intentioned.

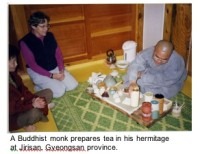

I have enjoyed very informal tea with Buddhist monks in Korea. A cloth-covered tray with small cups lined up next to a stack of small wooden coasters, a horizontal handled tea brewing pot, two lipped bowls for cooling, a source of hot water and a box of tea and good will is all that is necessary. We joked and he poured. Laugh. Pour.

It has taken Korean over 50 years to reconstruct and appreciate its own unique Way of Tea. The vast majority of Koreans would rather drink small paper cups of instant coffee prepared with creamer and lots of sugar and to sit at Starbucks or a French pastry cafe. Now, through the efforts of such men and women of tea, Korea’s cultural traditions are finding their way to a renaissance and broad interpretation.

While we’re waiting, we can enjoy a cup of tea. Hold the “fuss”.

Photographs: Lauren W. Deutsch

Copyright held by the author

(better images will be uploaded soon)